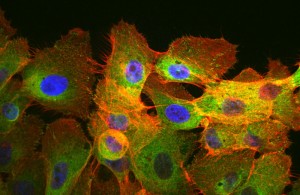

Image: A group of human mammary epithelial cells expands asymmetrically on a surface of increasing rigidity (towards the right of the image). Color lines correspond to the tracks followed by each cell (gray dots) for 10h

In 2000, researchers at Boston University and the University of Massachusetts first proposed that the stiffness of a tissue could guide the movement of isolated cells. However, subsequent studies showed that this experimental mechanism was very inefficient. “We’ve now found that when cells cooperate with each other, they are able to respond to variations in tissue stiffness so much more efficiently than when they are isolated,” says Raimon Sunyer, first author of the IBEC study.

“It’s an example of collective intelligence: a group can carry out a task that their isolated individuals are unable to perform,” says Xavier Trepat, ICREA researcher at IBEC, and leader of the study. “The key is not in any property of the individual, but in their interaction with their peers.” In this case, the interaction is physical, cells transmit information between them by means of forces.

The research team, which also includes members from the UB, the UPC, the University of Zaragoza, CIBER-BBN and CIBERES, developed new techniques to create biomaterials with variations in stiffness, and used these to observe which cell groups preferentially moved to the more rigid areas. The larger the group, the more efficient the movement; and individual cells were unable to find their way to the most rigid areas.

The researchers developed a theory explaining the phenomenon, naming it collective durotaxis. “Each cell applies a force to its environment that allows it to measure the surrounding stiffness. But cells need to physically interact with each other to transmit this information collectively in order to move,” says Pere Roca-Cusachs, IBEC researcher, professor at the University of Barcelona and co-leader of the study.

“Tumors are more rigid than their surroundings, so collective durotaxis can explain the mechanisms by which tumor cells move to initiate the metastatic process,” says Xavier. “Similarly, scars are also more rigid than their surrounding tissues. We believe that collective durotaxis is a key mechanism to explain how cells move to heal wounds, and that it could help us to work out how to control metastasis.”

—

Source article: Raimon Sunyer, Vito Conte, Jorge Escribano, Alberto Elosegui-Artola, Anna Labernadie, Leo Valon, Daniel Navajas, Jose Manuel Garcia-Aznar, José J Munoz, Pere Roca-Cusachs and Xavier Trepat (2016). Collective durotaxis cell emerges from long-range force intercellular transmission. Science, Vol. 353, Issue 6304, pp. 1157-1161